Businesses and workers are changing the kinds of demands that are put on a place. The public sector still needs to catch up.

Leadership, engagement, change: These were the themes that speakers at the Redevelopment Forum plenary session on Making Every Place a Great Place To Live and Work emphasized as critical to successful redevelopment in the face of shifting economic trends.

Jennifer Vey, the director of Brookings Institution’s newly established Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking, set the stage with some historical context (view her presentation here) and a look at how recent technology and economic shifts — desire for professional collaboration, demand for easy access to amenities, potential for remote work — are changing the demands that are put on a place.

By and large, she said, businesses and workers have embraced these changes. Governments, however, may have some catching up to do. “We are constrained by policies, practices and investment structures that have failed to keep up with the changing needs of firms, institutions and workers, hampering the scope of their impact,” she said. We need new knowledge about firms and workers and their changing demands, to help plan and prioritize public investments; new practices and tools that grow local businesses and jobs and foster access to opportunities; and new policies and investment strategies — new land use, zoning, economic development strategies, and infrastructure — that will break down silos and support innovative places and placemaking.

Eugene Diaz, founder and principal of Prism Capital Partners, echoed this. While businesses used to consider only the costs of relocation, he finds that now they are focused on the war for talent, and are willing to pay more to be in a place where talent wants to work. Convenience of lifestyle is a corporate relocation mantra, he said — workers don’t want 40-minute commutes, or to have to drive to lunch; they want a range of amenities within easy reach. Residents, he said, want to be part of a community, which creates a need for new types of housing and amenities.

However, Diaz observed, municipalities have been slower to embrace these changes. When developers look at where to allocate capital, he said, they are still fighting the same battles over the same issues — local resistance to change, new residents, and the effect of new residents on schools. He called on municipalities to exhibit strong leadership in order to help residents understand the benefits of embracing these changes, and to move forward with a plan of economic redevelopment that capitalizes on them.

Aisha Glover, president and chief executive officer of the Newark Alliance, emphasized the importance of innovative strategies. She noted that Newark is now focusing on bringing housing to its downtown to support retail, developing more open space and parks, and making its downtown more of a 24-hour destination. More importantly, she said, the city is trying to move away from its historical tendency to focus on individual projects, which she said does a disservice to the city and to its residents, and is moving instead to marketing the downtown core as a unified innovation district. The important lesson from the Amazon HQ2 process, she said, is the need to take the lead in marketing the entire city, rather than letting developers or brokers sell individual sites or projects.

Paterson Mayor Andre Sayegh is adopting a similar strategy. Paterson, he said, has identified several “catalytic zones” on which to focus revitalization, including its downtown and the train station. With greater density and a mix of uses, these areas can attract Millennials and the next generation, coming up behind them. Leverage a place’s legacy assets, he said, and transform them into legacy projects.

New Jersey Economic Development Authority Chief Executive Officer Tim Sullivan said the state fully understands the need for a more diverse, targeted and comprehensive approach to economic development, and for greater support for locally driven efforts. Place, he said, is an essential ingredient of a 21st century economy that is singularly focused on talent. Businesses’ top concerns are: Can they find talent, and can those people get to and from work reliably and conveniently? There should be a bigger variety of opportunities within a place for living, working, and playing that people of all ages want.

State vs. Local, Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up

Diaz emphasized that while a strong state partnership is critical, we need to stop thinking of economic development as only a state-level issue. It is a local issue, he said; it starts on the ground. He spoke directly to the local officials in the audience: “If your town hasn’t densified around transit, hasn’t densified and mixed downtown uses, you’re derelict.” Towns need to consider form-based codes and other paradigm changes to real estate development in these areas. If they don’t, he said, “you’re behind the curve and you’re already losing.”

However, he acknowledged that human nature tends not to like or understand change, so it takes powerful, strong leadership to show people where the world is going. And while you need the community involved, he said, beware the small minority that yells the loudest. Be sure all voices are at the table.

No One Left Behind

Vey acknowledged that the benefits of the new knowledge economy are not equally distributed, and that too many people and places are being left behind. The knowledge economy favors tech occupations, putting communities with comparatively less access to educational opportunity — especially younger members of those communities who will replace Baby Boomers as they retire — at a disadvantage, and creating a drag on long-term economic growth.

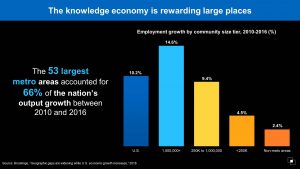

This inequality is affecting places as well as people, she said. Large, global centers are being rewarded by the digital economy, attracting innovative companies and educated workers, while smaller places struggle to keep up. (See chart). This phenomenon is also true within metros, and is exacerbated by housing and education disparities — decline and disinvestment in some places, accelerating unaffordability in others, including those typically near jobs.

If current trends are to work for more people, she said, the public, private and civic sectors will all need to make transformative investments in placemaking, including not just physical design but housing, education and workforce development, and job creation. The need is urgent, she stressed, but the opportunity is great.

Sullivan agreed, saying that EDA needs to diversify the partners it works with. The best ideas, he said, spring up from close to the ground, where people know what they need. The state needs to connect at that level, not just at a big corporation/big city level. This requires thinking about partnering in a different way; as a result, EDA is now offering planning money to enable communities to build their own economic development strategies. More inclusive planning, he said, brings more inclusive development.

Glover reiterated the importance of engaging a community in an authentic way. The state defers to the city defers to the community, she said, and gave as an example the city’s newly established Newark People’s Assembly, which allows residents to make recommendations directly to the city. Not only does authentic engagement help lay the groundwork for greater trust, she pointed out, it also provides better feedback.

Vey finished by emphasizing that we must focus on ways to generate widespread, locally led prosperity in economic districts of all sizes and types, including those with a concentration of assets that have been historically overlooked. Mixing uses, densification, and forward-thinking redevelopment can happen at all scales, she emphasized. We must understand that legacy assets — whether suburban office parks or our older urban areas — are being viewed differently by the market, and then we need to find ways to take advantage of that.